William Harvey Gray's history was the second biography that I wrote, back in 2012. He is my husband's great great grandfather.

The

Biography of

William

Harvey Gray

Civil

War Veteran

By

Ann M Sinton, Copyright, 2012

Biography of

William Harvey Gray (1838 – 1907)

Civil War

Veteran

William

Harvey Gray was born June 4, 1838 in Standing Stone, Bradford County,

Pennsylvania. He was the 3rd

of 7 children of Oliver Spicer Gray and Elvira Rosengrants. Not many details are known of his early life,

other than he was supposed to have been raised by his uncle, Abisha Woodward

Gray, until he enlisted in the army to fight in the Civil War at about age 23. [1]

In 1840, William lived in Herrick Township in Bradford County with his parents

and three siblings. According to the 1850 census of Standing

Stone, William was an 11 year old living with his parents, Oliver and Elvira,

along with his two brothers, Jeremiah and Jonas, and two sisters, Lucy and Mary

Jane. He is shown as attending school

that year. A third brother, Robert, was

born in Jun of 1850 and the fourth brother, Silas, in Jan of 1853. William’s father died in Dec of 1853. By 1860, William and his mother are listed in

the census living with a Crocker family in Bridgewater, Susquehanna County,

Pennsylvania, William as a farm laborer and his mother as a domestic. But it would appear that the family had been

broken up, possibly due to the death of William’s father. The 1860 census shows the eldest Jeremiah, as

already married with a family and living in Herrick, Bradford County, PA and

also Lucy was married with a three year old child living in Bradford, PA. Lucy’s husband would die that year and she

would quickly remarry. Jonas is 24, but

cannot be found in this census. Younger

sister Mary Jane, 16, is found living with a Seaborn family in Rush Twp.

Susquehanna County on the same census page as her Uncle Abisha Gray and her

maternal grandparents Alfred & Amy Estus.

This would at least indicate that they were neighbors. 10 year old Robert cannot be found but is

known to have lived until 1882. And

Silas, age 7, is living with his Uncle John Winthrop Gray in Dimock,

Susquehanna County, PA. [2]

On April 12, 1861, the

first shot of the Civil War was fired at Ft. Sumpter, South Carolina. Just 4 days later, William Harvey Gray

enlisted in one of the first Regiments that was organized in Pennsylvania, a 3

month Regiment, the 25th under Capt. Alfred Dart. His discharge papers show him as a private in

Co K, enrolled on the 16th of April 1861 and discharged on 26 July

1861. He was 23 years old, 5 feet 8

inches tall, with a light complexion, grey eyes and light hair. His occupation upon enrollment was that of a

farmer. [3]

At the start of the Civil War, the call for recruits went answered by men of all walks of life, patriotism being the main motivator for enlistment. Regiments were formed by state and enlistment periods ran anywhere from 3 months to 3 years. When attempting to form local units, public gatherings were scheduled complete with speeches, flag waving, bands, and veterans of previous wars. Some states were able to provide some of the uniforms for the men but women’s sewing groups were counted upon to clothe their soldiers as well. Gray was a favorite color in the early part of the war, causing much confusion during some battles as both North and South used the color. Equipment ran the gamut from obsolete muskets to the modern Sharps rifle. The initial encampment of the company was usually located in their home community which would allow family visits. The first activity would be the election of officers for the company. Captains and Leuitenants were chosen by the men. Training while the company was still in the home area varied. When the time came for the company to depart, the men were granted a furlough to say their goodbyes to family and friends. The actual departure of the unit was a public affair usually marked by a parade thru town. The men would then board a train or boat that would carry them to their final training destination.

The day began with reveille at about 5

or 6 a.m. There was roll call, breakfast

call, sick call, call for guard duty, then drill call and dinner call - all

before noon. The men had a short period

of free time after their meal then came more drilling. Companies were dismissed in late afternoon,

but their work was not over. The men had

to brush their uniforms, polish shoes and brass in preparation for the nightly

retreat exercises which included another roll call, inspection of the troops

and a dress parade. Supper call followed

this and then yet another roll call after which the men were ordered to their

quarters. Taps was the final call of the

day. The drills for new recruits were

made up of mostly handling arms and practicing maneuvers. Often mock skirmishes were held. The men’s main shelter was the tent. There were several types, some held 12 men

and some as little as 4 men. The men

were also issued a haversack. This held

his cartridge box, bayonet, blankets, canteen, and knapsack. The knapsack held clothing, stationery,

photos, personal hygiene items, books, and other personal items. There were also food implements either packed

on the knapsack or hooked to the soldier’s belt. On top of everything was the winter overcoat,

an extra burden, often discarded to lighten the weight of the pack which could

weigh as much as 40 or 50 pounds. Once

the initial wave of emotion wore off, the day to day routines quickly became

the source of complaints over everything from camp conditions to missing family. Many desertions took place as the war

continued. Privates in the Union Army

were paid $13 per month, by the end of the war it was only up to $16. Regulations called for soldiers to be paid

every two months, but they were lucky to receive their pay at four month

intervals. [4]

In William’s three months of service,

the 25th’s many duties were guarding the Capitol of Washington

DC. Some companies of the 25th

served at Fort Washington, some performed guard duty at the Washington

Arsenal. After much instructional

drilling at the Arsenal, 5 companies, including William’s Co K, were ordered to

march to Rockville, Maryland and from there they proceeded to Poolesville and

finally encamped opposite to Harper’s Ferry, which was at the time occupied by

the Confederate Army. The company was moved here and there and by

the 18th of July they were back at Harper’s Ferry. On the 23rd of July the order

comes to proceed to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania to be discharged with thanks for

their patriotic service. [6]

Two of William’s brothers also

enlisted - Jeremiah in the 50th New York Engineers and Jonas in two

regiments, the 61st Pennsylvania Infantry and also the 141st

Pennsylvania Infantry. Jeremiah would

be injured having his leg shot off but survived to lead the local GAR post and

Jonas also survived, although he had injuries to his face. Both brothers fought at Gettysburg.

The United States Civil War Draft

Registration Records[7]

of 1863-1865 show that William, as of July 1, 1863, already has military

experience with the 4th Regiment of PA Volunteers. These records also show that he is married

and his occupation is that of a laborer.

This would be William’s first marriage.

His wife, Saloma Estus, born in 1841, is the daughter of Alfred Estus

and Amy Light. William and Saloma were

married on Jan 16, 1866, a date that does not match his Draft records.

William enlisted once more, this time

in a 3 year Regiment, the 4th Pennsylvania Reserve and was assigned

to Co H on the 22nd of Aug, 1861.

Co H of the 4th PA Reserves was made up of men from the

Susquehanna County area and was organized in June of 1861.

The 4th PA Reserves Regiment

Colors

The 4th PA Reserves Regiment

Colors

On Aug 25th, the Regiment

received orders to report to Washington DC where they camped 3 miles from

Georgetown. Their first battle would not

be until June 26, 1862 at Mechanicsville, VA where the 4th came

under fire but were not actively engaged as they were being held in

reserve. That night they moved to Gaines

Mill, VA where, on the 27th, they were attacked by the Rebel

Army. Overwhelmed, they were forced to

cross the Chickahominy River to avoid capture.

Here at Charles City Crossing, they were attacked again, having been

posted on the front line. The Union line held and the night of June 30, the

Regiment retired to Malvern Hill. During

these seven days of battle the 4th PA Reserves Regiment lost over

200 men. By August, the regiment was in

place to fight at Gainesville and then

also the 2nd battle at Manassas/Bull Run on Aug 30. A Union loss.

By Sept 14, they were part of the Maryland Campaign and fought at South

Mountain under Gen. Meade. Another victory.

This led them to become involved in the Civil War’s bloodiest battle

---- Antietam on Sept 16. They fought

that day and the next. Over 6000 were

killed but William survived. They spent

most of Oct in Maryland and then moved to Falmouth, VA until Nov 19. Their next

battle would be at Fredericksburg on Dec 12.

They were said to have fought bravely but Meade’s lines became confused

and had to retreat. [8]

By

Feb 1863, the 4th was greatly reduced in numbers and was ordered

back to Washington to rest and recruit.

They stayed here until Jan 1864, when they were ordered to West

Virginia. They left Washington on B

& O Railroad boxcars and arrived in Martinsburg, WV 2 days later. While in West Virginia, the 4th’s

duties took them to Harper’s Ferry and back and also to Parkersburg, the

Kanawha Valley, Fayette, Rocky Gap, to a battle at Cloyd’s Mountain against a

Confederate Army of 4000 men. The Union

forces prevailed. From here they

proceeded to the New River at Dublin for a night crossing and camped near

Blacksburg, Virginia for a night. After

many skirmishes in West Virginia, the 4th was ordered to return to

Pennsylvania for mustering out as their 3 year term was up. It was May 1864. On June 4th, they boarded a

steamer bound for Pittsburgh, where the veterans received a welcome from the

grateful citizens of Pittsburgh. They

arrived at Philadelphia 4 days later where they were mustered out on June 15,

1864. William’s company was reorganized

and he reenlisted into the new Co A.

Once again the company skirmished throughout western Virginia towards

West Virginia. At one point in late June

(22nd), the company, after a retreat, had marched all day without

food and were one hundred miles from supplies.

The foodless march lasted for 5 days when one soldier had foraged a ham

large enough to share but not enough to satisfy. By July, they were in West Virginia in the

vicinity of the Gauley River and Charleston.

The 4th PA Reserves Monument at Antietam, Maryland

The 4th PA Reserves Monument at Antietam, Maryland

At this point, the Company was consolidated in a Co L and attached to the 54th Pennsylvania Volunteers. On July 14th, they broke camp and crossed the Potomac River. By the end of July the company had lost nearly half of it’s men to either sickness or in battle. Now part of the Army of West Virginia, 8th Army Corps, the Company took up position at Winchester where a battle was fought on Sept 19th ending in a Union victory. The next morning they moved toward Cedar Creek. They pushed back the rebels several times. By Oct 10th, they were in position to support General Custer’s Cavalry. The charge was successful, but their forces fell back to Cedar Creek. On Oct 19, 1864, at 4 AM, the enemy attacked with a rebel yell and swarmed down upon the unsuspecting Yankee troops. Those who were not killed or taken prisoner fled. 1200 men were lost and William Harvey Gray was among those taken prisoner. [9]

Left - The 54th Pennsylvania

Infantry National colors flag – The national color was found rolled up within

the remnant of the 54th’s first state color.

William H Gray’s Company Muster Roll

Cards for the months of Sept & Oct

show him as missing in action Oct 19, 1864 near Cedar Creek. Then again the months of Jan & Feb 1865

as absent and missing in action. By the

Mar & Apr 1865 Muster Roll, he is shown as “absent sick in General Hospital

since March 1, 1865”. [10]

Drawing found at: https://www.facebook.com/companya54thpa

Cedar Creek Battlefield Foundation

The Confederate surprise attack was virtually complete and most of the Army of West Virginia troops were caught unprepared in their camps. The Confederates' quiet approach was aided by the presence of heavy fog. Kershaw's Division attacked the trenches of Col. Joseph Thoburn's division at 5 a.m. A few minutes later, Gordon's column attacked the position of Col. Rutherford B. Hayes's division. Crook's division-sized "army" was overwhelmed and many fled, half-dressed, in panic.

A brigade under Col. Thomas Wildes was one of the more alert units, and it conducted a fighting withdrawal over 30 minutes to the Valley Pike. Heroic leadership by Capt. Henry A. du Pont, acting chief of Crook's artillery, saved nine of his sixteen cannons while he kept them in action, stalling the Confederate advance, eventually establishing a rallying point for the Union north of Middletown.#ccbf #civilwarhistory

After William was captured, he was brought from Lynchburg, Virginia to be confined in a tobacco warehouse at Richmond, Virginia on Oct 23, 1864. He was sent to Salisbury Prison in North Carolina about Nov 4, 1864 after passing thru Andersonville Prison. William would spend the winter at Salisbury. He arrived at the worst possible time. The prison consisted of a collection of buildings enclosed by a wooden fence on an almost 6 acre site meant to house only 2500 men. When William arrived, there were 10,000 men housed there. By that time all of the buildings were used solely for hospital purposes. There was a shortage of medicine and food due to a Naval blockade. The 10,000 men were forced to spend a cold wet winter out in the open. The death rate was 28%. The survivors had to fight dysentery, pneumonia, smallpox, lice, scurvy, and dengue fever in addition to the starvation. Salisbury rivaled Andersonville in it’s living conditions and reputation. As recorded in several diaries kept by men held prisoner at Salisbury during the time William was also there, the conditions nothing short of horrific. Meals regularly consisted of rice soup. Meat, flour, and bread were not a daily part of the fare. A loaf of bread would have to be shared among many men. Meals were served once a day. Rations were routinely cut back by this point in the war and by late Nov 1863, the prisoners were receiving ¼ rations. The winter weather took it’s toll as well, even tho they were in the south the winters were cold and wet. Not a day would go by that didn’t have dead men carried out and buried in mass burial trenches. William would survive and thru a recently approved exchange program was paroled near Wilmington, North Carolina on Feb 28, 1865. The prison was eventually burned to the ground and is now the Salisbury National Cemetery. [11] [12] [13]

The above map shows some tobacco warehouses

in Richmond, Virginia near Libby Prison.

William Harvey Gray was held in a Richmond tobacco warehouse after he

was captured at Cedar Creek, Virginia.

Andersonville Prison, where William Harvey

Gray says he passed thru on the way to Salisbury Prison

1864 Illustration of Salisbury Prison

This is the time frame when William would

have been held at this prison. The men

had to live outdoors year round and dug holes about three feet deep which were

covered with a mud-thatched roof for shelter.

One had to sit or lie down inside.

Depiction of an escape attempt at Salisbury

Prison on Nov 25, 1864

This escape attempt would have taken place

just after William arrived at Salisbury.

It is not known if he participated or not. Eighty one men were killed in the attempt.

Salisbury Prison Hospital scene

Drawing of Salisbury Prison

Salisbury Prison Property Maps

Unknown Federal prisoner after his liberation from a Civil War Prison – from the Library of Congress

Although William was only held prisoner for about 7 months, he may very well have been in a similar condition to the soldier above. William’s records say that he went into Salisbury Prison weighing 157 ½ pounds and left the prison weighing just 90 pounds. [15]

The photo above is of sisters, Amy & Alice Gray. They were William’s nieces. Amy and her father, Abisha W Gray, helped take care of William when he was trying to get home on furlough after being released from prison. He was able to get as far as Danville, Pennsylvania before falling so ill that he could not continue his trip.

William was at the Parole Camp at Annapolis,

Maryland when he was given a 30 day

furlough which he used to journey back home

to Susquehanna County Pennsylvania, but was taken sick on the way and

was “taken off the car to a hotel in Danville, Pennsylvania” on March 15, 1865.

William was delirious for two days and was suffering from typhoid fever,

diarrhea, difficulty breathing, heart palpitations and was severely emaciated. The physician treating him, Dr Simington,

thought he would not live for more than a few days. But William did survive and

lay sick there for 6 or 7 weeks under the care of Dr Simington, who was able to

have his furlough extended several times to allow William to recover and go

home. His cousin, Amy Gray Williams and

her father A W Gray, went to Danville to care for him. Afterwards William was at his Uncle’s house

for several months and not able to get around without much difficulty. William did receive orders to return to his

Company, which he did on May 31, 1865 at Annapolis, Maryland. Three days later he received his discharge

from the army.

William Harvey Gray's Service Documents

After his discharge, William suffered

from rheumatism and heart disease which left him unable to do much work for

more than three years. William’s pension

records begin about 1865 when he applies for a government pension. His physical description paints a man who is

5 feet 8 inches tall weighing 143 lbs and has a fair complexion. William received a pension of $4 a month

beginning June 1, 1865. This was

increased on Jan 5, 1885, after many medical exams and letters from former

comrades in the army and family and friends who could attest to William’s

condition both before his incarceration and afterwards, to $8 a month. Each

time that William would apply for an increase in his pension he would have to

have a medical exam and provide affidavits from friends and family on his need

for the increase. William did receive

increases on Apr 16, 1890 to $12 a month, on Jul 29, 1891 to $17 a month, and

on Oct 17, 1905 to $24 a month. As of

May 4, 1907, William was still receiving $24 a month. [16]

William’s family was growing thru all

of these trying times. His first child,

Gary Newton, was born in Dec of 1867 and Alfred William in Nov of 1868.

In the 1870 Census, William and his

wife, Saloma, are living near the Auburn 4 Corners Post Office in Rush

Township, Susquehanna county with 2 children, Gary Newton age 3 and Alfred

Woodward age 1. William’s occupation is

that of a farmer. The value of his

personal estate is $300. In 1873, their

third child is born, Ezra F.

In 1880, William was again working as a

laborer with Saloma keeping house in Exeter, Luzerne county, Pennsylvania. Saloma would die on May 6, 1886 and William

remarried almost immediately, probably because he had three children to take

care of. His second wife was Mary A.

Ammick, whom he married on Oct 25, 1886.

Even though the 1890 census

has been lost, William is counted on the 1890 Veterans Schedule which did

survive. At this time he is living in

Beaumont, Wyoming County, Pennsylvania.

A disability listed as “loss of health” from being in Salisbury Prison

during the war. His rank was a Private

in Co’s A,F, and K in Regiments 4th, 34th and 25nd in PA Reserve, dates of

enlistment shown are Apr 16, 1861 – July 16, 1861; Aug 22, 1861 – Jan 18, 1864;

Jan 19, 1864 – May 31, 1865 with lengths of service shown as 2 yrs 3 months 29

days and 1 year 7 months.

The last census record

where William is recorded, is 1900, where he and his wife Mary are living in

Noxon Township, Wyoming county, Pennsylvania.

They have been married for 13 years by now. William, now 62 years old, is working as a

day laborer with only one month that year without work. He is shown to be able to read and write as

well.

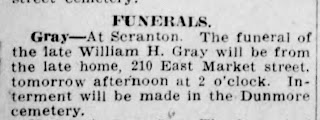

At the time of his death,

on May 8, 1907, William was a widower, Mary having died sometime before 1905. He was living at 210 E Market St, Scranton,

Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania with his son, Gary Newton Gray, [17]and

left 3 sons and 4 grandchildren behind.

He would count 8 grandchildren, 10 great grandchildren, 15 great great

grandchildren, 18 great great great grandchildren, and 12 great great great great grandchildren

known as of 2012.

Wilkes Barre Record, March 10, 1899

The Wilkes Barre Semi Weekly Record, July 21, 1905

The Wilkes Barre Record, May 19, 1906

The Scranton Truth, May 9, 1907

One

of the final records of William is a Veterans Burial Card[19]

that shows his burial place as Dunmore Cemetery in Dunmore, Pennsylvania. He is buried in Block 9 Lot 31 with a

government provided headstone due to his service in the Army. Although no stone has been found to

date. William’s death certificate shows

his cause of death was heart disease with acute indigestion contributing to his

demise.

William Harvey Gray is my husband, Tom

Sinton’s, Great Great Grandfather.

Sources for William

Harvey Gray Biography

1.

“Jonas

Latham Gray & his wife Lucy Spicer – Their Ancestors and Descendents” by

Rev. Garford Flavel Williams, Nicholson,Pennsylvania.

2.

“The

Conception, Organization, and Campaigns of Co H 4th Pennsylvania

Reserve Volunteer Corps, 33 Regimental Line, 1861-5”, Historian, Sgt M H

VanSCoten, compiled by Mrs M H France; Baldwin & Chapman Publishers,

Tunkhannock, Wyoming County, Pennsylvania. Online at: http://www.retaylor.org

3.

www.history.army.mil/books/staff-rides/cedarcreek.htm

4.

Original

Certificates of Service and Discharge Papers – provided by Oscar M Sinton Jr,

Tamaqua, Pennsylvania

5.

Ancestry.com

Census Images – 1840 thru 1900

6.

Ancestry.com

– US Civil War Draft Registration Records, 1863-1865

7.

History

of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-1865, published 1870

8.

National

Archives, Washington DC – original Pension records of William Harvey Gray

9.

www.gorowam.com/salisburyprison

11.

www.salisburyNC.gov/prison

12. Wikipedia.com – Salisbury Prison

13. www.civilwar.nygenweb.net/regiments/jamesbaileydiary.html - Salisbury Prison diary

14. “Eye of the Storm”, Private Robert

Knox Sneden, The Free Press, 2000.

15. Oscar M Sinton, Jr

16. “The Life of Billy Yank – Common

Soldier of the Union”, Bell Irwin Wiley, Louisiana State University Press,

1952.

18. Ancestry.com – Veterans Burial Cards

database

19. Ancestry.com – Forsman Family Tree

20. William Harvey Gray’s original Death

certificate

21.

http://www.pareserves.com/?q=node/41 - flag

photos

22.

www.stonesentinels.com –

monument photo

23.

Library of Congress

PlPlease give credit and post a link to my blog if you intend to use any of the information written here. My blog posts are © Ann M Sinton 2025. All rights reserved

No comments:

Post a Comment